There cannot be a more agreed upon problem in aviation.

Every single airline, every single flight: the most critical information about that flight is passed to the pilots in the style of a Telegram from the early 1900’s. Coded, abbreviated, often undecipherable, upper case chunks of text: the least human-friendly format imaginable.

A news story in 2013 declared “Plug pulled on the world’s last commercial electric telegraph system”.

Shhh. Don’t tell them. Not true. Our NOTAM system — used to tell crews about changes and dangers on todays flight — is still proudly flying the flag. We use the ITA-2 International Telegraph Alphabet character set from 1924, instead of ASCII, which the rest of the world switched to in 1963.

We use Q-codes (from 1909) to categorize the message. We use abbreviations heavily, because it costs more money to send messages in plain text format. Wait, scratch that — that logic ended in the 90’s because, well, the internet.

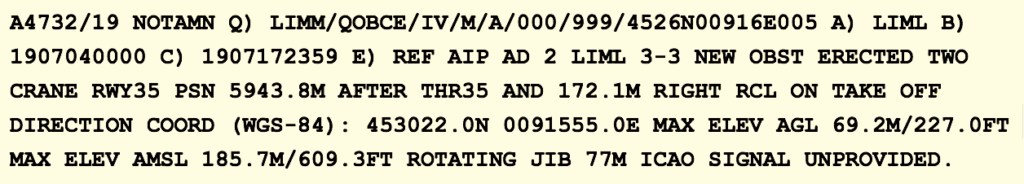

And so, while the passenger is choosing emojis for their last What’sApp message before the aircraft doors close, in the cockpit the pilot is deciphering what the impact of this Telegram might be:

If that seems tough to get through, now consider what 50 pages of it looks like:

That is the average size of the Notam Briefing package that each crew is given.

And so, your job as a pilot at briefing time, is to find the one Notam that will end your career or endanger the aircraft, in a package the same size as a short novel. Buried deep in Birds of Bangkok, War and Peace by Greece and Turkey, Unlighted Tiny Obstacles, Goat grazing times, Grass cutting timetables — is a runway closed, a diversion airport unavailable, a decision height changed. And you’ll miss it.

Air Canada 759 missed the one telling them that 28L was closed in San Fransisco, so they tried to land on the taxiway. Only an alert United crew prevented the worst crash in American history, and then only by 14 feet, or 1 second. That led to the NTSB to declare “Notams are Garbage”.

From the Final NTSB Report: “Concerns about legal liability rather than operational necessity, drive the current system to list every possible Notice to Airmen (Notam) that could, even under the most unlikely circumstance, affect a flight. The current system prioritizes protecting the regulatory authorities and airports. It lays an impossibly heavy burden on individual pilots, crews and dispatchers to sort through literally dozens of irrelevant items to find the critical or merely important ones. When one is invariably missed, and a violation or incident occurs, the pilot is blamed for not finding the needle in the haystack!”

Thank you, Robert Sumwalt, for calling the problem out.

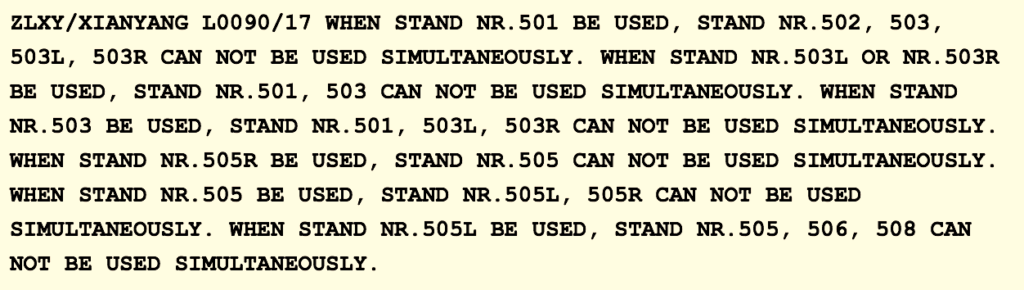

It’s not just the volume, or readability — it’s the Mensa-level problem solving skills required to parse the contents. Answer this question: If you’re on Parking Stand 505 Right, can someone else use Stand 503 Left?

If you did figure it out, how long did it take? Now multiply that time by 250, a straw-poll average number of Notams in a briefing. Think this is manageable in the 20 minutes the crew have to brief the flight?

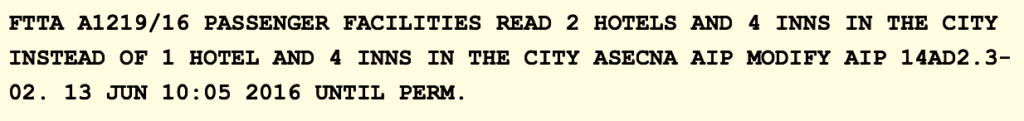

In 2007, the annual count of Notams reached 500,000. This year, 2019, we are on track for 2 million Notams. The problem is intensifying, and rapidly. We are drowning in the data, but missing the message. Every change imaginable is stuffed into the system:

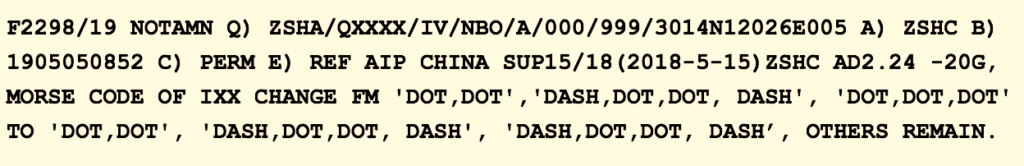

And this Chinese entry is the best one of 2019 so far …

Say it out loud.

In 1964, Flight International published a snippet from the FAA, declaring that the Notam system was being revamped, and from March 15th that year only essential, critical Notams would be allowed to remain. That was 55 years ago. We’ve tried, and we’ve failed, many, many times, to solve the problem.

But — enough about the problem. If you are a pilot, dispatcher, or controller, you know only too well the problem, and its impact.

How about we talk about how we find the solution instead?

Let’s start here.

The NOTAM problem needs to be seen from the primary user perspective – namely pilots, and dispatchers. It affects us every day, because we know that one day, we’ll be bitten by it.

We’re fixing it because we want it to change.

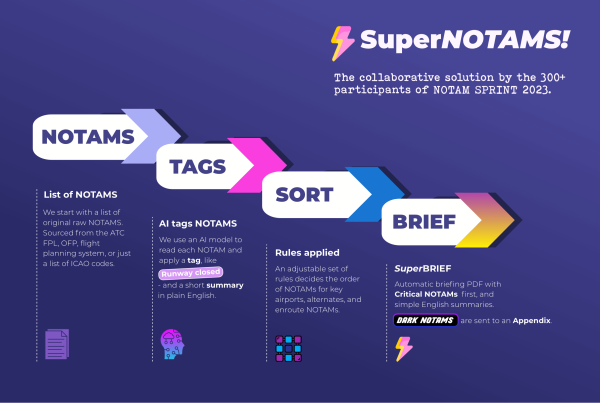

Most importantly, we’re fixing it as a community, collaborating to create the space to allow the solution to come.

Zooming out a little, if we look at this as not an aviation problem, but a communication problem, it becomes less unique, less challenging. Many bigger problems have been solved by looking at them differently.

So we’re going to collaborate with smart thinkers, problem solvers, designers, coders, creatives. We’re going to work together as people, rather than agencies or companies. We’re going to jump into a process that might be messy, challenging, difficult, and will often seem impossible.

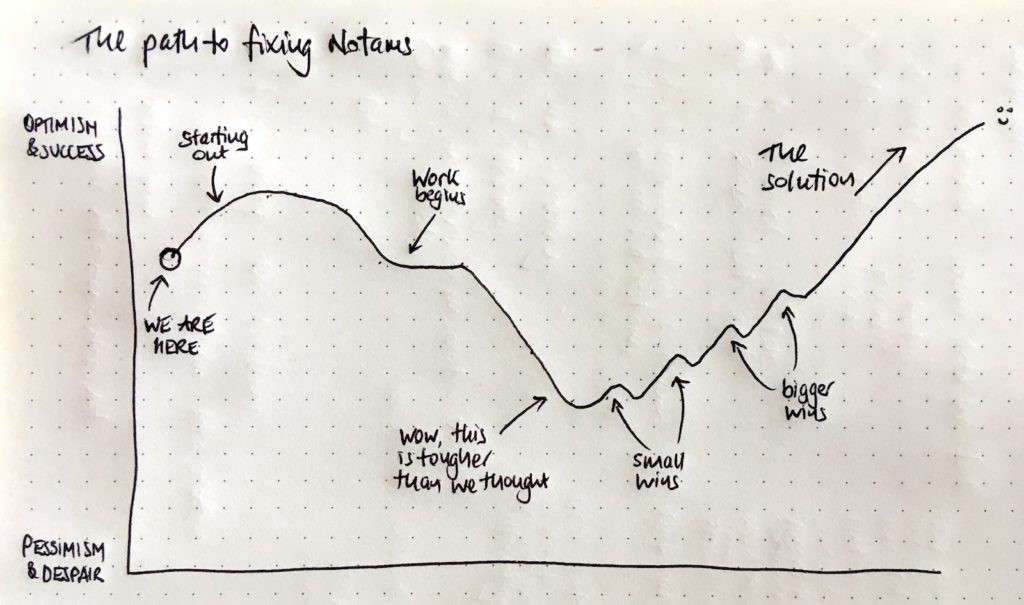

As per this handy graph I’ve drawn:

Don’t join us to force change — this is the change. Don’t join us to shout louder — this problem is bigger than any one agency or organization. Don’t join us if you think this is someone else’s problem to fix — it’s our problem, and we’ll fix it together.

The first step is creating the space for this magic to happen. Join us if you have no idea how to solve it yet, but you have positive energy to contribute.

The Notam Team needs you!

The first part of the process is the gathering, the coming together. We’ll start with the first and most important step — creating that space for the solution. Figuring out how best to collaborate, invite creativity in, think differently. Then, the research — the science, the data, the hard facts. Identify the problem, and the impact. And from there … well, it’s unwritten. Not knowing is part of the approach. Oh, and we’re going to have fun. There’s no creativity without fun.

I believe the problem is eminently solvable, but only as a community. I hope you’ll join us!

Mark Zee.

A Brave and long waited initiative. It bears my full support.